- Home ›

- Digital Post Services ›

- Evolution of Postal Tariffs

The Evolution of Postal Tariffs

How terminal dues and changing rate systems reflect international developments and shape the global postal network

At A Glance

The Universal Postal Union (UPU),

founded by the Treaty of Bern of 1874, is a specialized agency of the United

Nations (UN). It coordinates postal policies among its member countries and

their designated postal operators (DO) to create a single, global postal

territory for the reciprocal exchange of postal items. This article explores how its system of setting postal tariffs has developed over the past 50 years.

1971: The introduction of Terminal Dues

In July 1971, the UPU adopted a system in which the sending country pays the receiving country a compensation fee for handling, delivering and (if required) customs clearance of international mail.

The rates paid to the designated operator (DO) of the receiving country were called terminal dues. They could be applied when mail followed UPU standards, forms and codes, and the flow between the DO used specific, clearly defined post offices (Offices of Exchange).

This was the first formalized compensation scheme setting postal tariffs for DO to provide these services. It had previously been assumed that such a scheme was unnecessary as export and import flows – and therefore payments – would largely balance each other out. This assumption was quickly shown to be unrealistic due to the various postal markets being at different stages of development.

These terminal dues were not negotiated or contracted between the postal services, but instead calculated and determined by the UPU.

Although there have always been other parallel bilateral and multilateral arrangements in place between the individual DO, the majority of mail volumes were handled using the network and clearing model of terminal dues designed specifically for the UPU.

This model also provided a basic digital infrastructure for the exchange of data related to tracking, customs clearance and clearing (IT systems such as IPS/CDS/IFS) at cost.

As postal volumes and competition grew, this simple model soon changed massively:

- Direct market entry: The underlying principle of the UPU model for cross-border mail – with each country’s DO sending cross-border mail directly to the DO in the destination country for local delivery – began to be bypassed. Large, initially mainly European, DO started to enter foreign markets directly, where they acquired customers and volumes, often via their own commercial subsidiaries (e.g., Deutsche Post – DHL, La Poste – DPD).

- Growth of ecommerce: Originally created for the exchange of letter mail (“letters containing matters of correspondence”), the postal system evolved with the growth in commercial items (“letters containing goods or merchandize”) to become the dominant postal tariff model for developing cross-border ecommerce.

1999: Changing the rate calculations

1. Starting point: kilo rates

In its first 30 years from 1971 to 2000, terminal dues consisted of a fixed rate per kilogramme and applied to all DO equally.

Naturally, this model failed to account for the different cost structures in the destination countries, and the fact that delivering ten 100g items generates a different level of costs than a single 1kg item.

2. Next step: item/kilo rates referenced to domestic tariffs

In 1999, the UPU decided to introduce a per-item and per-kilogramme rate for postal items.

- The rates were set annually by the UPU and calculated according to a complex model which referenced domestic postal tariffs.

- Part of the remuneration was linked to the Quality of Service (lead-time; % of items delivered within J+5 or J+3).

- Each country was assigned to one of four groups (1 to 4) according to its development status, and this determined its level of payment to the respective destination country for delivery.

- The rates were set in SDR (“Special Drawing Rights”), an international reserve asset, created and managed by the IMF.

- Both rates and SDR exchange rates were fixed in advance and remained valid for one year.

However, this tariff model was still problematic from the viewpoint of the importing countries.

As a result of the item/kilo model, lightweight import shipments, in particular, became considerably cheaper for the sender than the corresponding domestic shipments, as domestic rates usually assigned a fixed price within a weight interval and within specific dimensions.

In addition, the world's largest and most developed ecommerce export market, China, was still able to use tariff discounts based on its historical status as a developing country.

China quickly grew to become by far the largest ecommerce market and the largest exporter of ecommerce shipments. The old UPU model supported developing countries by stipulating lower terminal dues in the destination country. Traditionally designated a developing country, China, in particular, had long benefited from these cost advantages, a status that was being increasingly criticised by importing countries, especially the US.

Added to that, huge volumes of small packets were being rerouted via developing countries that paid lower outbound rates.

Consequently, the model needed to be adjusted once more.

2019: UPU increases postal tariffs

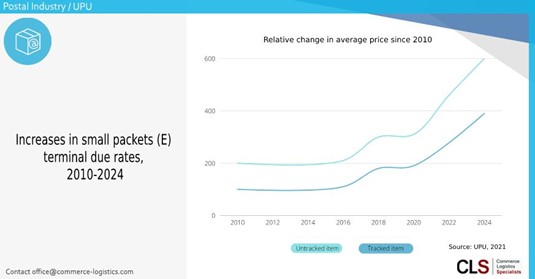

Starting 2016, UPU terminal due rates were gradually increased to correct this imbalance. Finally, largely due to pressure from the USA, the system was fundamentally adjusted in 2019.

- DO were allowed to charge self-declared, country-specific rates, limited to a maximum of 70% of the corresponding domestic tariffs, with the increase spread over several years.

- An additional regulation for “big” countries (primarily demanded by, and tailor-made for, the USA) allowed terminal dues to be immediately raised to the level of the new model.

Although the new model was fairer ̶ at least from the standpoint of the major importing countries ̶ unsurprisingly, it led to another significant decrease in volumes transacted through the UPU system.

The increased UPU postal tariffs made the classic UPU model less competitive. This was later compounded by other factors, most notably the 2021 EU VAT Ecommerce Package, with European DOs charging high customs clearance fees for "Delivery Duty Unpaid" (DDU).

Huge increase in direct entry based on bilateral contracts and commercial solutions

As a result of these changes, the DO individual tariff models became more important.

Here – in contrast to the basic UPU model in which a DO is primarily responsible for mailers in its domestic market – volumes are acquired abroad (often through partners and subsidiaries), cleared through customs, released for final delivery in all of the EU, and then forwarded to postal operators in the destination country on the basis of bilateral and multilateral agreements.

Source: UPU 2021

Source: UPU 20212021: The new EU Customs & VAT model

On 1 July 2021, the EU VAT eCommerce Package changed the EU’s VAT and customs regime.

All inbound consignments (including postal items) are now subject to VAT, exemption limits have been abolished, and all items must be presented to customs digitally in advance.

The UPU postal tariff

model allows DO in destination countries to

charge fees for the:

- customs clearance process (presentation to customs), and

- the collection of any duties.

However, unlike the item/kilo rates which must reflect real costs, these additional charges can be set almost freely by the DO.

While these fees were almost irrelevant prior to 1 July 2021 – almost all items in the postal channel had a value of less than EUR 22 and therefore fell below the exemption thresholds – these fees now apply to all items.

New UPU customs fees are a "lethal blow" to the UPU DDU model in the EU

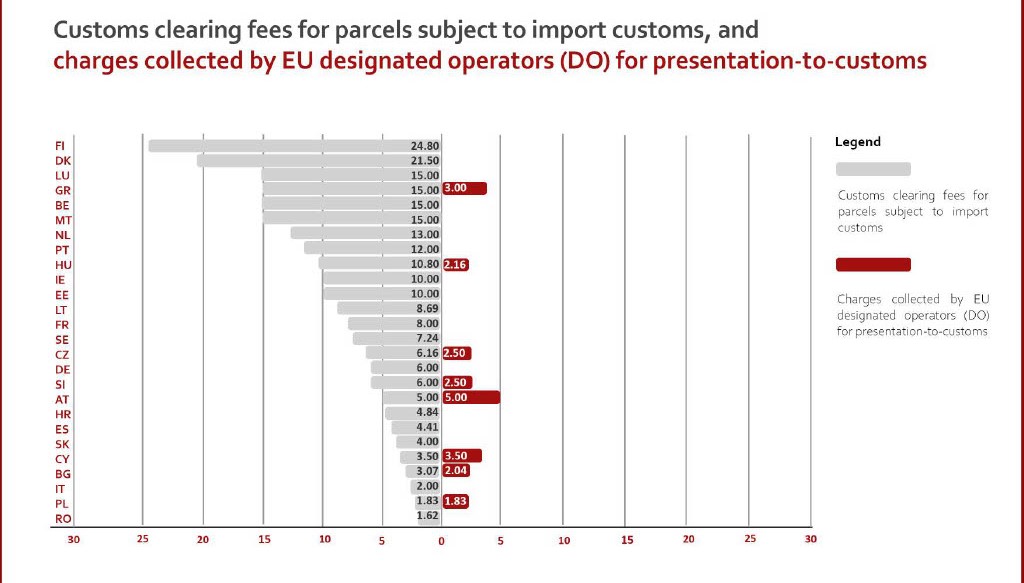

The fees for collecting VAT on Delivery Duty Unpaid (DDU) items can be extremely high: some EU DOs charge anything up to €25 per transaction.

Additionally, some DOs now also charge high fees for processing fully digital, simplified customs clearance – even where there are no duties to collect and IOSS is used (see the chart below).

Fees calculated for a postal consignment with a value of EUR 10; all fees in EUR.

Source: UPU / Parcel Post Compendium (As of 1 April 2022).

Fees calculated for a postal consignment with a value of EUR 10; all fees in EUR.

Source: UPU / Parcel Post Compendium (As of 1 April 2022).As a result:

- Volumes in the UPU channel have fallen by more than half, with postal DDU items becoming commercially unattractive;

- Major marketplaces (electronic interfaces) are using the IOSS model, clearing customs themselves and handing over the already cleared shipments to the domestic DO outside the UPU channel;

- The B2B2C customs and shipping model has become increasingly relevant; and

- Bilateral postal

contracts or agreements with online merchants and marketplaces offer a cost

advantage compared to UPU postal tariffs.

So where does that leave us?

In short, a new, fragmented, and highly digital postal sector is changing the relevance and application of the UPU postal tariff model.

The developments described in this article outline the evolution of the postal sector – from a closed, highly regulated model, to the rise of alternative but also largely closed multilateral and bilateral systems, to the current endpoint of a highly digitised global industry in which designated postal operators (DO) are part of the supply chain, and Wider Postal Sector Players (WPSP) play a crucial role by offering an almost unmanageable number of shipping solutions and tariffs (i.e., direct entry, B2B2C).

The reality is that these developments have massively reduced the importance of traditional UPU postal tariffs. It is no coincidence that volumes in the UPU channel have fallen by more than half. This is due to:

- The rise of alternative tariff models such as that of the IPC;

- The interests of individual DO who have themselves built up global networks in parallel with the UPU;

- And the rise of commercial alternatives to the established DO.

However, this does not mean that UPU postal tariffs are becoming irrelevant.

A new role for the UPU

Although the UPU’s postal tariff model is no longer dominant, we believe the UPU itself will thrive by focusing on its other strengths. Not only does it remain the only global exchange system owned and controlled by national states, but the UPU also operates a globally standardized digital infrastructure that is ideally suited as a backbone for cross-border ecommerce shipping.

We believe that the UPU global postal system will be increasingly used as a central "tariff exchange", and that the UPU could act as an (informal) standardization authority for postal tariffs, especially after the UPU opens up to WPSP. Individual tariffs can already be deposited in the UPU system.

In addition, UPU tariffs will continue to provide a backup for small and medium countries or their DO: the market, by its very nature, disadvantages stakeholders with little market power, while the UPU was established to maintain a global universal service, with UPU postal tariffs (bilateral or commercial) remaining relevant for these flows.

Top image courtesy of Prometheus on Unsplash

- Home ›

- Digital Post Services ›

- Evolution of Postal Tariffs

Does this article cover a topic relevant to your business? Access the CLS Business Lounge for the market intelligence you need to stay ahead of the crowd. Find out more