- Home ›

- Standards & Regulations ›

- UPU vs. EU Standards

UPU vs. Single European Market For Postal Services

At A Glance

- Proposed EU regulation for electronic identification and trust services is too little and too late. The solution? Walter Trezek argues that the EU should adopt Universal Postal Union standards already established for digital services and open them up to the European market. This avoids the creation of parallel and conflicting standards.

The UPU is establishing a global framework for digital postal services

The extension of the postal service provision being driven by the Universal Postal Union creates a comprehensive global, cross-border and cross-sector framework for e-identification, authentication, and related postal (document, direct marketing, parcel and financial) trust services.

Since 2008 the designated operators (DOs) have been actively changing their business model from an item-driven to a data-driven model.

Adopting best practices from the world of ecommerce and digitally-driven online platforms and ecosystems, the UPU now provides its members with the necessary governance and regulatory framework to extend existing cross-border and cross-sector trust services into the digital communication and logistics environment.

Authentication is everything

In a data-driven environment every postal service will have to authenticate the sender and recipient prior to any cross-network (cross-border and cross-sector communication and data driven logistics) exchange of documents, data, goods and services. Protecting the integrity and the privacy of mail items is a fundamental part of the postal service provision.

It is therefore no surprise that authenticating the “postal service user[1]” is at the core of the postal service provision in general, including its current extension into the digital world.

The EU wants the digital environment to be open to all

Like the Universal Postal Union, the EU also wants its citizens to be able to conduct business safely and securely in the digital sphere.

However, whereas the former serves only the interests of the national incumbents, the philosophy behind EU legislation is to create a barrier-free, single market in the digital environment.

When it comes to digital services, the European Commission makes a core distinction between Digital Identity and Electronic Identification.

Digital identity

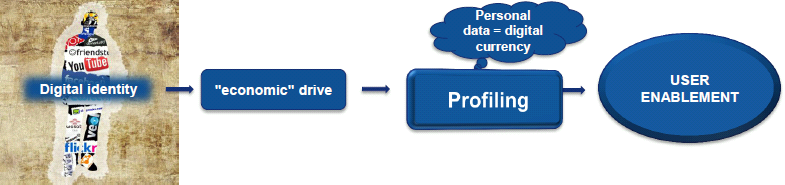

Fig. 1: Explanation used by EC DG Connect for eIDAS WS, September 25, 2013

If we look at Figure 1, digital identity consists of data provided (direct or indirect consent[2]) by consumers in the process of using digital communications and services. In most cases this data enables third parties to profile the individual, or collective behaviour, and, to a certain extent, to re-identify users on particular sites in the digital world.

Users expect to be tracked; more and more users understand that profiling their behaviour is a way of indirectly paying for services accessed without direct payment; third parties sell this information to advertisers and profiling companies.

As more data becomes available, cross-referencing, including the scanning of content in open email communications, not only allows big data to analyse past behaviour but also to produce qualified predictions into the future behaviour of groups of consumers and individuals. The individual consumer becomes powerless to control his personal data.

The European Union’s new data protection framework aims to give back to consumers the power to control their own data.

Electronic

Identification

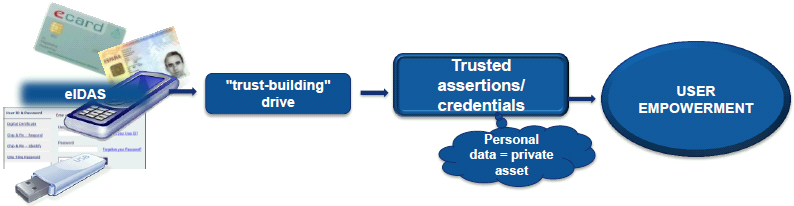

Fig. 2: Explanation used by EC DG Connect for eIDAS WS, September 25, 2013

Electronic identification makes the digital world go round.

A solid and sustainable trust framework is needed to leverage on the huge potential offered by the digital society. Without trusted credentials, moving the single market into the digital 21st century will not work.

In most European countries the interior ministries are the gateway for identification and credentials: proving that a person (or even a legal entity) exists requires governance and regulations to build the necessary trust framework. But by no means does it stop there.

The race to become a trust broker

Shifting identification from its current physical basis (passport, ID card, etc.) to digital means will raise efficiency to unprecedented levels. Moving from the analogue to the digital economy fundamentally changes the way we do business. As businesses become data-driven, authenticating the partners in any transaction becomes an essential part of the business itself.

Not only must we be able to trust the identity, we must also be able to trust the attributes of that identity: GENDER, AGE, CREDIBILITY, LOCATION, certain RIGHTS to access SERVICES and acquire GOODS, CREDIT RATING, etc.

This information can be acquired via cross-referencing digital identities, but this requires the “informed consent” of the authenticated person (or legal entity). This leads to the emergence of trust frameworks, acting as mediators and enabling transactions in a digital environment.

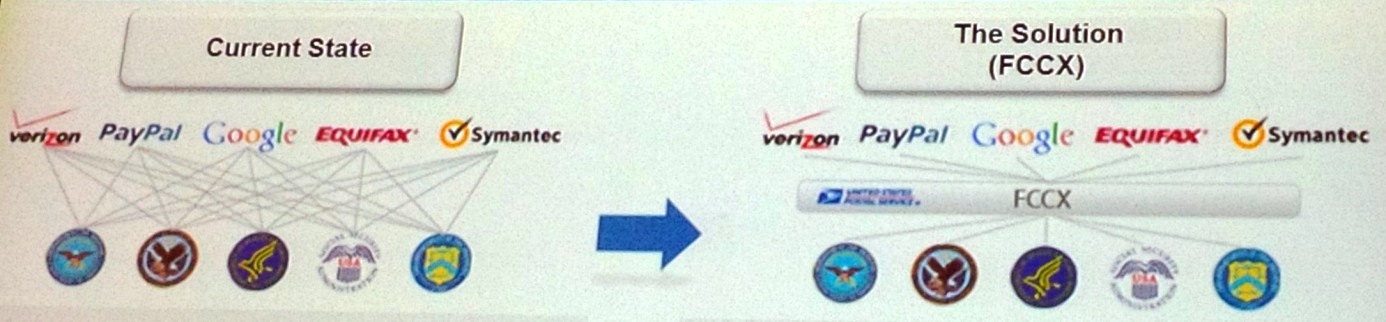

Fig. 3: USPS: Allowing federal agencies in the USA to securely interact with a single trusted “broker” to authenticate customers

The UPU’s aim is that, by extending the postal service provision into the digital age, postal services take on this role as the broker of trust frameworks.

An example is shown in Figure 3: here the United States Postal Service (USPS) plans to extend its trusted mediator role in analogue item-based exchange services to the digital world. It offers a centralized interface between agencies and credential providers, based on a trust framework for e-identification, authentication, and related postal (document [direct marketing and media], parcel and financial) trust services.

Conflicting standards

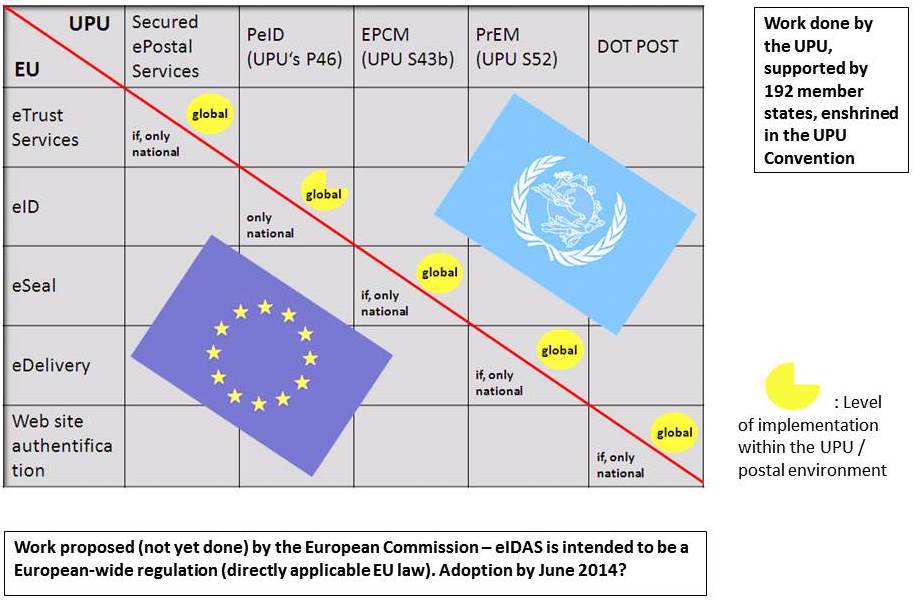

Thus the Universal Postal Union and EU essentially share a similar goal – to establish a regulatory and governance framework for trust and cross-sector cooperation in the digital world.

Yet if we look at the European Commission’s current eIDAS proposal[3] and compare it with work already done by the UPU, we could argue that the UPU is well ahead of the European Commission:

A sensible way forward

As UPU standards are exclusively applicable to the designated operators (national incumbents), they represent a de facto limitation to the concept of a single European market.

However, considering the UPU’s head start in this field, no EU regulation on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market can ignore UPU standards, established ecosystems and cross-sector and cross-border applications.

A feasible way of avoiding parallel and conflicting standardisation - and preventing postal incumbents from transferring their current market dominance into the digital sphere – would be for the EU to adopt and actively shape UPU standards for an EU context. This is the only way the EU can keep the market open and finally establish a single, internal market for digital services within the EU.

Walter Trezek is Chairman of the Consultative Committtee (CC) at the UPU, and CEN Liaison officer on

European postal standardization

Footnotes:

[1] The UPU Convention

defines the Postal Service User in Art 1.3bis: “Personal data: information

needed to identify a postal service user”

This definition (adopted by the 25th UPU Congress) is the

same in part as that contained in article 2 of the Postal Payment Services

Agreement. It conforms to the definitions given in international and regional

regulations concerning the handling of personal data, and adapts them to the

postal context. It relates mainly to personal data on the sender and addressee

of a postal item. The term "identification data" refers to all data

enabling the person concerned to be identified directly or indirectly. In the

case of postal data, this means their name and physical address. In the case of

postal electronic Identification, this means data (including specific

attributes required by relying parties in an online transaction) to

authenticate postal service users.

[2]Please note the most recent document

by the “Working Party under article 29 of Directive 95/46/EC” – so called WP

29; Working

Document 02/2013 providing guidance on obtaining consent for cookies”,

adopted Oct. 2, 2013

[3]Proposal for a Regulation on Electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market [COM(2012) 238 final]

- Home ›

- Standards & Regulations ›

- UPU vs. EU Standards

Does this article cover a topic relevant to your business? Access the CLS Business Lounge for the market intelligence you need to stay ahead of the crowd. Find out more